We know it as the Battle of Little Big Horn, or "Custer's Last Stand". Native Americans know it as the Battle of the Greasy Grass. It is quite possibly the most legendary military engagement in US history. Like the maiden voyage of the Titanic, everyone knows how this story ends.

Or do they?

But in the annals of military history, farriers, veterinarians and horseshoers are often a footnote in the records, at best. Finding out who they were and how they served can be a challenge. Sadly, one of the few records kept is when they died in service.

None died more tragically than those who followed General George Custer across the grassy plains of southeastern Montana in June 1876. They met the combined forces of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes out on that rolling grassland.

Farriers Benjamin Brandon of Kentucky, Vincent Charley of Switzerland, and Benjamin Wells of Illinois all died at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

|

| Vincent Charley's grave marker at the battle site. His name was misspelled on his marker. David Graham photo. |

Charley's death is well documented. Under the command of Captain Thomas Weir, he was part of Troop D's ill-fated attempt to rescue Custer. The 27-year-old was the first wounded, taking one or multiple shots through the hips while advancing on horseback. Weir and his men left Charley behind. He tried to crawl through the grass behind them. He was advised to hide in a ravine. Charley's body was found with a stick rammed down his throat.

What may well be Charley's remains were exhumed by archeologists in the 1990s; they matched his reported wounds with those seen on a skeleton, and tentatively identified it as his. He died a long way from his birthplace in Lucerne, Switzerland and may have had second thoughts about where he ended up; before the battle, he had gone AWOL and was court-martialed. However, his term of service ended just a few months before his death, but he re-enlisted the following day. At least 12 other Swiss immigrants died with him that day, including a blacksmith and a saddler.

|

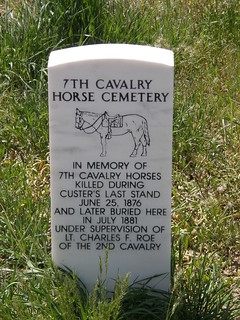

Custer's men were said to have shot their

horses to use as shields for protection. Others were killed during the advance. The horses have their own cemetery area at the

battle site. (Jim Bowen photo)

|

But Custer's 7th Cavalry Regiment had more farriers on its roster. Only 68 men survived but among them were English farrier John Fitzgerald, German farriers John Bringes and John Steinker, Ohio farrier James Moore and Wisconsin farrier Able Spencer.

Fitzgerald, from Staffordshire, England, had served with the Union forces as a farrier during the Civil War. His record on the day of the battle only states that his horse became exhausted, so he retreated. He survived, unscathed, and continued to serve as an army farrier until 1890.

Mysteriously, farrier William Heath, a former coachman from Staffordshire, England, is reported to have both died in Custer’s column and to have survived for decades afterwards, depending on whose account you accept. His military records state that Heath had been unable to work in the months before the march out from Fort Abraham Lincoln, since he had been kicked in the head by a horse.

His story, if indeed he really was there and/or did survive, has stimulated many imaginations. He is the subject of a book published in 2003, Billy Heath: The Man Who Survived Custer's Last Stand.

Billy Heath is unique among men: He has two tombstones, one in the grasslands of Montana and one back home in Pennsylvania, where he is documented to have fathered seven children after returning from the battle.

|

One of the stables at Custer's headquarters at Fort Abraham Lincoln in North Dakota has been reconstructed. Photo by Larry Syverson.

|

Charles A. Stein was senior veterinarian for the Seventh Cavalry. Educated at the University of Hannover in Germany, he arrived with a herd of mules at Fort Abraham Lincoln in April, just before Custer set off on his campaign into the grasslands. Stein inspected all the horses before the departure, culling out some who were unfit. As a result, 64 unfortunate soldiers were forced to march on foot.

During the march, Stein inspected the horses daily; he shot a mule who was found to have the highly contagious disease known as glanders. Along the way, Major Reno complained that his horses were leg weary and in need of shoes; the horses were placed on half rations, in spite of the hard march and conditions. Pack trains followed the columns of cavalry with supplies, but apparently grain was in short supply.

Stein remained behind when Custer led the main force toward the battle on June 22.

Soon after the battle, Stein resigned his commission and moved to St Paul, Minnesota, where he continued to practice veterinary medicine. He never published a memoir of his march with Custer.

What about Custer's farriers who didn't head out on the march from Fort Abraham Lincoln that June? English farrier John Marshall was sick and stayed behind; among his orders was to tend the garden until the troops returned. He deserted a few years later and no record of the rest of his life is available.

During the march, Stein inspected the horses daily; he shot a mule who was found to have the highly contagious disease known as glanders. Along the way, Major Reno complained that his horses were leg weary and in need of shoes; the horses were placed on half rations, in spite of the hard march and conditions. Pack trains followed the columns of cavalry with supplies, but apparently grain was in short supply.

|

| The interior of the stables at Fort Abraham Lincoln, where the farriers would have worked, is beautifully captured by Dustin White. |

Stein remained behind when Custer led the main force toward the battle on June 22.

Soon after the battle, Stein resigned his commission and moved to St Paul, Minnesota, where he continued to practice veterinary medicine. He never published a memoir of his march with Custer.

What about Custer's farriers who didn't head out on the march from Fort Abraham Lincoln that June? English farrier John Marshall was sick and stayed behind; among his orders was to tend the garden until the troops returned. He deserted a few years later and no record of the rest of his life is available.

Farriers John Rivers and William Woods, both from New York, were on detached service at the time.

General Custer, once considered a military hero and brilliant strategist, became the epitome of ridicule and foolhardiness in American culture, but there is much more to the story of his last battle than mere arrogance and ill-advised decision-making: There are the stories of the men from all backgrounds and nationalities who fell with him.

Those who had no choice but to follow Custer should not be forgotten

Top photo of the battle site by Robert Montgomery, via Flickr.com (CC by 2.0).

_____________________________________________________

To learn more:

History Mystery: Laminitis on the Little Big Horn (Hoof Blog archives)

The actual events that transpired at the battle are difficult to verify. Some scholars have gone to great lengths to collect or interpret facts, but there are still many versions of what actually happened.

Vincent Charley's (assumed) remains are documented in this book: Soren Blau and Douglas H. Ubelaker, editors. "Handbook of Forensic Anthropology and Archaeology." (2016): 229-230.

The actual events that transpired at the battle are difficult to verify. Some scholars have gone to great lengths to collect or interpret facts, but there are still many versions of what actually happened.

Vincent Charley's (assumed) remains are documented in this book: Soren Blau and Douglas H. Ubelaker, editors. "Handbook of Forensic Anthropology and Archaeology." (2016): 229-230.

The Swiss soldiers and horsemen are documented in this paper:

Winkler, Albert, "The Swiss at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, 1876" (2011). Brigham Young University Faculty Publication #1812.

Genovese, Vincent J. Billy Heath: The Man who Survived Custer's Last Stand. Prometheus Books, 2003.

Gray, J. S. (1977). Veterinary Service on Custer’s Last Campaign. Kansas Historical Quarterly, 249–263.

Men with Custer is a comprehensive website about British-born men who marched with Custer in June 1876. Author Peter Russell has researched biographical details on each.

Winkler, Albert, "The Swiss at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, 1876" (2011). Brigham Young University Faculty Publication #1812.

Genovese, Vincent J. Billy Heath: The Man who Survived Custer's Last Stand. Prometheus Books, 2003.

Gray, J. S. (1977). Veterinary Service on Custer’s Last Campaign. Kansas Historical Quarterly, 249–263.

Men with Custer is a comprehensive website about British-born men who marched with Custer in June 1876. Author Peter Russell has researched biographical details on each.

_____________________________________________________

|

| Click here to learn more about the HoofSearch guide to equine hoof research. Click here to subscribe and begin reading today. |

© Fran Jurga and Hoofcare Publishing; Fran Jurga's Hoof Blog is the news service for Hoofcare and Lameness Publishing. Please, no re-use of text or images on other sites or social media without permission--please link instead. (Please ask if you need help.) The Hoof Blog may be read online at the blog page, checked via RSS feed, or received via a headlines-link email (requires signup in box at top right of blog page). Use the little envelope symbol below to email this article to others. The "translator" tool in the right sidebar will convert this article (roughly) to the language of your choice. To share this article on Facebook and other social media, click on the small symbols below the labels. Be sure to "like" the Hoofcare and Lameness Facebook page and click on "get notifications" under the page's "like" button to keep up with the hoof news on Facebook. Questions or problems with the Hoof Blog? Click here to send an email hoofblog@gmail.com.

Follow Hoofcare + Lameness on Twitter: @HoofBlog

Read this blog's headlines on the Hoofcare + Lameness Facebook Page

Disclosure of Material Connection: The Hoof Blog (Hoofcare Publishing) has not received any direct compensation for writing this post. Hoofcare Publishing has no material connection to the brands, products, or services mentioned, other than products and services of Hoofcare Publishing. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.