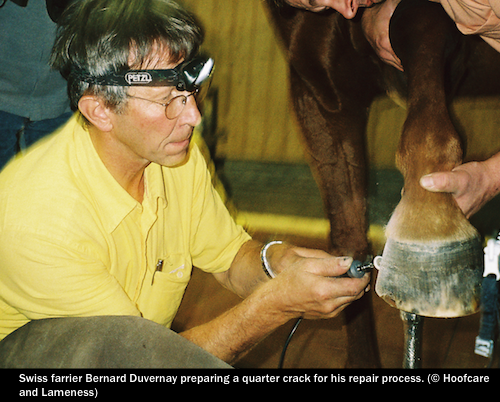

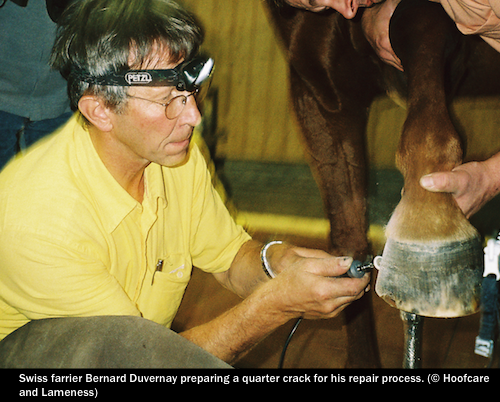

This is an example of a quarter crack repair by lacing technique, using stainless steel sutures threaded through tiny and shallow guide holes drilled with a very fine drill bit. The idea is not to shut the crack but to hold it open and stabilize it so that any infection or "heat" can dissipate before a patch is applied. Quarter cracks have varying risks for infection and may or may not be associated with an abscess somewhere else under the hoof wall. The new complete hoof wall grows down from the hairline, much as you grow a new fingernail. (Ian McKinlay photo)

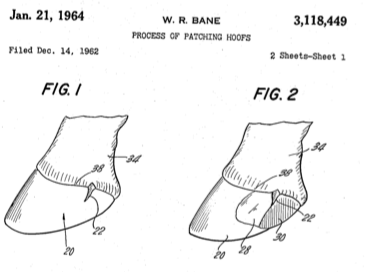

Farriers have been stitching and clamping quarter cracks together for well over 100 years now, but a unique “modern” quarter crack patch was patented in 1964 by an enterprising Los Angeles racetrack horseshoer named William R. Bane.

At first, Bane offered to patch horses for free, just to get the word out. Bane's first patch was on the Thoroughbred Destructor, trained by John Nerud.

A horseshoer based at southern California tracks, Bane enjoyed early success with a champion Thoroughbred aptly named "Prove It." Once patched, Prove It won six stakes races in a row, including the Hollywood Gold Cup.

It was enough of a big deal to be written up as a headline story in the New York Times.

Bane’s plan had been to train others at racetracks around the country, much like a franchise, but he ended up spending a lot of time on airplanes because owners and trainers wanted him to personally patch their horses.

Bane’s patented secret turned out to be to cover the cleaned crack with a synthetic rubber called Neolite, a material very popular in the early 1960s for rubber-soled shoes, which were quite a sensation at the time.

In 1962, Bane was called east to work on Su Mac Lad, who at that time was the world’s all-time high-money winning trotter. It took Bane eight hours to patch that crack for trainer Stanley Dancer, but Su Mac Lad was training the next day and raced a week later. He went on to be United States Harness Horse of the Year, with a patched hoof. He raced an impressive 151 times in his life; Bane patched him six times. The 1960s were the heyday of harness racing in the United States, and Su Mac Lad is still revered for his racing record.

Bane charged $250 for his patches in 1962, plus his travel expenses.

The steps listed for Su Mac Lad’s eight-hour ordeal were:

1. remove some of the wall behind the crack

2. reshoe the horse;

3. apply the rubber;

4. apply plastic cement;

5. wrap with tape;

6. heat treatment for an unspecified time;

7. remove the tape;

8. finish the patch to conform to hoof wall contour.

Fiberglas eventually gained popularity over Bane's rubbery patch, and then in the 1990s, two-part polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) adhesives came along for rebuilding walls, shoring up weak heels, and covering cracks after they were dry.

Eventually, Buckpasser came back to racing and won just about everything, with 15 consecutive victories, setting track records and earnings records as he went, in spite of a recurring crack.

I should mention that 13 (by my count) of those victories where in the second half of 1966 alone. Many horses today may not have that many starts in a lifetime, let alone do it on a cracked foot.

Buckpasser was never actually patched by Bane. He did fly from California to Florida to examine the horse days after the crack was noticed following the colt's victory in the Flamingo in March. Bane determined that the crack was infected and should not be patched right away. He stayed and checked the foot repeatedly, waiting for it dry up. He refused to patch it until he deemed it free of infection.

Bane went back to California. Buckpasser ended up eventually being "patched" by Louis Grasso, an auto-body mechanic and sometimes harness horseshoer from The Bronx, who had some success patching Standardbreds.

Before the 1992 Belmont, the New York Racing Association had to issue a press release denying that A.P. Indy was lame. Conspiracy theories sprang up when he was secretly vanned to a different racetrack to train without an audience. When Joey removed A.P. Indy's bar shoe before the race, and replaced it with a regular plate, it was news. (And he won.)

Penn Vet's Dr Bill Moyer claimed to have worked on 74 different cases of quarter cracks in one year. That would average out to more than six per month. He said that most were Standardbreds; Moyer received funding from Standardbred leader Billy Haughton to study crack repair. He loaded feet in a vise and found that the crack closed when the horse was weightbearing, and sometimes even overlapped, which would pinch tissue and cause a horse a lot of pain.

Quarter crack repair is still a task best left to the experts. Done incorrectly, a well-meaning lacing and/or patching job done at the wrong stage of crack therapy can seal in infection so that a major problem erupts.

In spite of the availability of skilled practitioners, in spite of advances in technology, and in spite of advanced medications and therapeutics, quarter crack recovery is still compromised by owners and trainers who fail to act quickly to intervene and who fail to appreciate the need for continued care and monitoring. A quarter crack is not a "fix it and forget it" problem for a horse; it can be a bump in the road for an equine athlete or a prolonged, painful lameness issue that limits a horse's career, value, and welfare.

© Fran Jurga and Hoofcare Publishing; Fran Jurga's Hoof Blog is the news service for Hoofcare and Lameness Publishing. Please, no use without permission. You only need to ask. This blog may be read online at the blog page, checked via RSS feed, or received via a headlines-link email (requires signup in box at top right of blog page). Questions or problems with this blog? Send email to hoofblog@gmail.com.

In January of 1964, the US Patent Office awarded him patent number 3118449, to protect his secret method for repairing cracked hooves of Thoroughbred and Standardbreds so they could race again--and win.

It was enough of a big deal to be written up as a headline story in the New York Times.

Bane’s plan had been to train others at racetracks around the country, much like a franchise, but he ended up spending a lot of time on airplanes because owners and trainers wanted him to personally patch their horses.

Bane’s patented secret turned out to be to cover the cleaned crack with a synthetic rubber called Neolite, a material very popular in the early 1960s for rubber-soled shoes, which were quite a sensation at the time.

In 1962, Bane was called east to work on Su Mac Lad, who at that time was the world’s all-time high-money winning trotter. It took Bane eight hours to patch that crack for trainer Stanley Dancer, but Su Mac Lad was training the next day and raced a week later. He went on to be United States Harness Horse of the Year, with a patched hoof. He raced an impressive 151 times in his life; Bane patched him six times. The 1960s were the heyday of harness racing in the United States, and Su Mac Lad is still revered for his racing record.

Bane charged $250 for his patches in 1962, plus his travel expenses.

The steps listed for Su Mac Lad’s eight-hour ordeal were:

1. remove some of the wall behind the crack

2. reshoe the horse;

3. apply the rubber;

4. apply plastic cement;

5. wrap with tape;

6. heat treatment for an unspecified time;

7. remove the tape;

8. finish the patch to conform to hoof wall contour.

Fiberglas eventually gained popularity over Bane's rubbery patch, and then in the 1990s, two-part polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) adhesives came along for rebuilding walls, shoring up weak heels, and covering cracks after they were dry.

According to newspaper reports of the day, Bane was also called in to patch Northern Dancer, who won the Kentucky Derby and Preakness while wearing a Bane patch.

But no horse is more associated with Bane--and with quarter cracks in general-- than the great Buckpasser, who sat out the 1966 Kentucky Derby and Preakness while newspapers chronicled his crack woes, and what Bill Bane thought and did. Or didn't do.

Eventually, Buckpasser came back to racing and won just about everything, with 15 consecutive victories, setting track records and earnings records as he went, in spite of a recurring crack.

|

Kentucky Derby and Preakness winner Big Brown in 2008; his cracks had cracks. (© Ian McKinlay photo) |

Buckpasser was never actually patched by Bane. He did fly from California to Florida to examine the horse days after the crack was noticed following the colt's victory in the Flamingo in March. Bane determined that the crack was infected and should not be patched right away. He stayed and checked the foot repeatedly, waiting for it dry up. He refused to patch it until he deemed it free of infection.

Bane also told the press that the crack was far back in the heel area, a difficult area to work on. Without a patch, the horse couldn't train.

A week later, a New York paper announced that the trainer admitted that Bane had not patched the horse, perhaps because of the unfortunate location or perhaps because of the persistent infection--or both. The world waited to see the great horse return to racing.

|

| Newsday (New York) headline |

Bane went back to California. Buckpasser ended up eventually being "patched" by Louis Grasso, an auto-body mechanic and sometimes harness horseshoer from The Bronx, who had some success patching Standardbreds.

Grasso's high-tech materials were actually variations of auto body repair materials, which he described as more of a coating than a patch, when applied to a cracked hoof. He called his material "Nu-Hoof".

Ultimately, the crack bothered the horse enough to warrant his retirement after one of the most successful US racing careers in history, including setting track records, in spite of the crack. His jockey, Braulio Baeza, told the trainer that the horse had had enough and was running on heart alone, not hooves.

Ultimately, the crack bothered the horse enough to warrant his retirement after one of the most successful US racing careers in history, including setting track records, in spite of the crack. His jockey, Braulio Baeza, told the trainer that the horse had had enough and was running on heart alone, not hooves.

|

Penn Vet farrier Rob Sigafoos pioneered multiple applications for polymers on the hoof. |

In the 1980s, the great Standardbred Nihilator raced with quarter cracks that were patched by farrier Joey Carroll. His heel was basically removed, and he wore a z-bar shoe.

In 1992, Carroll was in the news again, putting a patch on A.P. Indy before the Belmont Stakes that year, after the great horse sat out the Derby and Preakness, much like Buckpasser, while his foot healed.

Buckpasser's quarter crack experience in the mid-1960s came at the same time that researchers Jenny and Evans at the University of Pennsylvania's New Bolton Center were publishing papers in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association on their experiments with acrylics for hoof repair.

Twenty years later, Penn Vet farrier Rob Sigafoos continued their research with acrylics and polymers to not only patch hooves: Sigafoos had the first widely-recognized success with glueing cuffed shoes to the foot by using the hoof wall as the attachment site instead of the bottom of the foot.

|

| Professor Bill Moyer (file photo) |

Sigafoos and Moyer even collaborated on an instructional book.

The study of the hoof wall received a major boost in 1980, with the publication of Doug Leach's doctoral thesis at the University of Saskatchewan. "The structure and function of equine hoof wall" Importantly, in 1987, Canadian researchers Bertram and Gosline at the University of British Columbia delved into the structural properties of the hoof wall, as well as of keratin and the effects of moisture on wall strength.

Quarter crack repair is still a task best left to the experts. Done incorrectly, a well-meaning lacing and/or patching job done at the wrong stage of crack therapy can seal in infection so that a major problem erupts.

Or, it could impede normal growth from the coronet, causing a hoof deformity or a growth defect in that area. The goal of repair is a clean, dry crack growing out under the protective patch so that the horse is sound and pain-free.

Today, equine podiatry has advanced to the placement of drainage tubes under patches, as well as antibiotic-impregnated hoof repair materials. We still need a way to evaluate weightbearing in field and clinic conditions, before and after patching and during the rehabilitation period, to prevent subtle gait changes or imbalances that will affect healthy wall growth around the entire circumference of the coronet.

I am fortunate to have a great library of new and old books, as well as files that bulge with notes and proceedings from the hundreds of meetings I've attended, and (most of all) input from farriers and vets who generously share their cases, experiences, videos, and photos.

I am fortunate to have a great library of new and old books, as well as files that bulge with notes and proceedings from the hundreds of meetings I've attended, and (most of all) input from farriers and vets who generously share their cases, experiences, videos, and photos.

How different things were in Bill Bane's day. But one thing has not changed: Quarter cracks are still a challenge to a horse and everyone who tries to help.

In spite of the availability of skilled practitioners, in spite of advances in technology, and in spite of advanced medications and therapeutics, quarter crack recovery is still compromised by owners and trainers who fail to act quickly to intervene and who fail to appreciate the need for continued care and monitoring. A quarter crack is not a "fix it and forget it" problem for a horse; it can be a bump in the road for an equine athlete or a prolonged, painful lameness issue that limits a horse's career, value, and welfare.

|

| Click here for free signup for Hoof Blog newsletter updates. |

Read this blog's headlines on the Hoofcare + Lameness Facebook Page

Disclosure of Material Connection: The Hoof Blog (Hoofcare Publishing) has not received any direct compensation for writing this post. Hoofcare Publishing has no material connection to the brands, products, or services mentioned, other than products and services of Hoofcare Publishing. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.