You might have heard that the Budweiser Clydesdales will be missing from your television screens at Super Bowl LVII this Sunday in Arizona. The St Louis brewer will not run its traditional, expensive, and hugely popular ad featuring America's favorite team. (Yes, a hitch of giant Clydesdales are more beloved than either the Chiefs or the Eagles will ever be.)

But there will be a Budweiser Clydesdale commercial, you can be sure of that. It just might not be one that Budweiser wants America to see.

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, a.k.a. "PETA", is charging that Budweiser is guilty of cruelty for docking the tails of its Clydesdale horses. (PETA prefers to call docking "amputating".) So PETA is headed to the Super Bowl with a rolling billboard and a plan to disrupt the parade before the game. A plane will fly overhead with a "TAILGATE!" anti-docking message.

And a commercial will air, though whether it will be limited to the local Arizona market or shown nationally is not clear. Here's the Budweiser Clydesdale commercial no one--least of all Budweiser--was expecting to see this weekend:

You'll won't see Clydesdales cavorting with yellow Lab puppies this year. No Clydesdales leaping over canyons, either. No kickoffs with mighty hooves. And no sound effects of jingling harness, creaking wagons, and arched necks.

What's the fuss about tail docking? There isn't much of one, except at moments like this. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, tail docking is regulated or outright banned in 21 US states (but apparently not regulated in 29 other states). It is also banned in many countries around the world. More and more, it is identified as an American practice, even though it was once standard practice in many parts of the world.

Why are tails docked?

Tails are docked for the same reason that some dog breeds crop ears. It was once a fashion, and as the years passed, the "look" became synonymous with some breeds, especially the draft horse breeds. The fashion may have passed, but the look prevailed.

There was some rationale for the practice, since tails could become tangled in harness, and it is much easier to get the breeching over a horse's rump without a long tail. On a farm where a horse pulled mechanized equipment, farmers didn't want to risk a long tail getting caught in a hay tedder or rake.

There was some rationale for the practice, since tails could become tangled in harness, and it is much easier to get the breeching over a horse's rump without a long tail. On a farm where a horse pulled mechanized equipment, farmers didn't want to risk a long tail getting caught in a hay tedder or rake.

For foxhunters, a docked tail meant less time spent grooming, especially in the fall when briars and brambles from rough countryside could be tangled in tails.

But docking leaves the horse without a tail to defend itself against flies and to express estrus or behavioral signals. Some believe that horses feel pain in the tail stump, and that the lack of a tail can affect a horse's balance.

Who performs the docking?

It is possible to dock a horse's tail with tight rubber bands that cut off circulaton, and some breeders may still do that, if they are in a state where the practice is illegal, or if their veterinarians refused to do the surgery. The criminal code for tail docking is often a misdemeanor charge.

In the 1800s, tails were docked by farriers. When laws began around 1900, bounties were offered in New York City for witness testimony about tail docking. It became a secret underground practice done in remote sheds, far from prying eyes.

How do you dock a tail?

The AVMA defines docking as the amputation of the distal portion of the boney part of the tail. Docking typically leaves a tail approximately 15 cm (6 inches) long.Docking is a separate process from nicking, which refers to cutting tail tendons to cause an elevated carriage of the tail, often done for some non-draft show breeds.

A third process related to the tail is blocking, or numbing, the tail to cause it to hang limply, usually achieved by injecting alcohol into the tail close to major nerves. Again, this is done for show horses when an active tail would be penalized by judges.

|

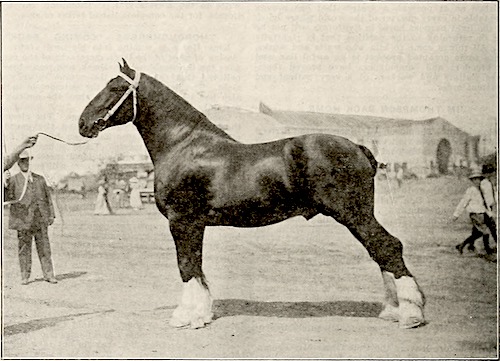

| A black Clydesdale in 1882, shown in the American magazine, Breeder and Sportsman. Notice the clean legs, with feathers on the front feet only and a docked tail. Feathers were not popular with American horsemen. |

According to the French history website The Horse and Its Culture, a guillotine-like device was sometimes used to slice off the tail in one swipe. The stub was cauterized with a hot iron. Horses in Paris had definite fashions for how their cropped tails were groomed and presented. The styles were known as the brush, the fan, the whistle, the crew and the ponytail.

The origin of the word "cocktail" is thought to be linked to a jaunty or cocky, energetic appearance of a horse with a docked tail, styled to resemble a cock rooster's upright tail.

Where do veterinarians stand?

The American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) has an official policy on docking tails, which is also endorsed by the AVMA:

"The American Association of Equine Practitioners condemns the alteration of the tail of the horse for cosmetic or competitive purposes. This includes, but is not limited to, docking, nicking (i.e., cutting) and blocking.

"When performed for cosmetic purposes, these procedures do not contribute to the health or welfare of the horse and are primarily used for gain in the show ring (nicking/cutting, blocking and docking) or because of historical custom (docking). If a horse's tail becomes injured or diseased and requires medical or surgical intervention, such care should be provided by a licensed veterinarian.

"When performed for cosmetic purposes, these procedures do not contribute to the health or welfare of the horse and are primarily used for gain in the show ring (nicking/cutting, blocking and docking) or because of historical custom (docking). If a horse's tail becomes injured or diseased and requires medical or surgical intervention, such care should be provided by a licensed veterinarian.

"The AAEP urges all breed associations and disciplines to establish and enforce guidelines to eliminate these practices and to educate their membership on the horse health risks they may create. Members of AAEP should educate their clients about the potential health risks, welfare concerns, and legal and/or regulatory ramifications regarding these procedures based on the relevant jurisdiction and/or association rules."

In many state laws, the decision to dock a horse's tail or not is left to the veterinarians. In the state of New Hampshire, anyone wishing to dock a tail needs to gain permission to do so from the state veterinarian.

In the United States, the Secretary of War outlawed the practice of tail docking for military horses in 1903. Read more about it in this clipping from the ASPCA magazine, Our Animal Friends, in 1904:

In the United States, the Secretary of War outlawed the practice of tail docking for military horses in 1903. Read more about it in this clipping from the ASPCA magazine, Our Animal Friends, in 1904:

The AVMA has position statements and advice to veterinarians on cosmetic altering of many types of farm and companion animals, from lambs to dogs and on to cattle and horses.

It's useful to know that practices vary between countries. This is especially true of dogs. Also, laws are changing in countries around the world. For instance, two weeks ago, an exposé by the BBC in the United Kingdom led to the banning of a dog show scheduled to be held for imported American "bully dogs" with altered ears. Not only is that ear-sculpting practice banned from being done to a dog in the UK, there is a movement afoot to make it illegal to import a dog into the UK if its ears have been altered.

In conclusion, Anheuser Busch is probably not breaking any laws by docking the tails of its foals. It is also possible that the breeding farm's veterinarians may feel strongly that full tails might be a hazard for horses or handlers, so the procedure is done on the foals. Or they might just be determined to maintain tradition.

One tradition that Budweiser did not maintain is their annual Clydesdale commercial during the Super Bowl, leaving the door open for others to use the hitch for their own publicity. A classic, heartwarming Budweiser Clydesdale commercial might have been cheaper, even at Super Bowl advertising prices.

To learn more, click on any of these links:

Antique French tools for tail docking

Dr. Sharon Cregier's extensive bibliography on tail docking sources

Dr. Sharon Cregier's extensive bibliography on tail docking sources

|

| Click here to sign up for easy email alerts for new articles on the Hoof Blog. |

© Fran Jurga and Hoofcare Publishing; you are reading the online news for Hoofcare and Lameness Publishing. Please, no re-use of text or images without permission--please share links or use social media sharing instead. (Please ask if you would like to receive permission to re-publish.)

Questions or problems with this site? Click here to send an email hoofblog@gmail.com.

Follow Hoofcare + Lameness on Twitter: @HoofBlog

Read this blog's headlines on the Hoofcare + Lameness Facebook Page

Enjoy images from via our Instagram account.

Disclosure of Material Connection: Hoofcare Publishing has not received any direct compensation for writing this post. Hoofcare Publishing has no material connection to third party brands, products, or services mentioned. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

_painting_in_high_resolution_by_John_Frederick_Herring._Original_from_Yale_University_Art_Gallery%20x500.jpg)