Showing posts with label military. Show all posts

Showing posts with label military. Show all posts

Sunday, March 16, 2014

Sunday, April 21, 2013

Lieutenant Boniface's Lost Notes on Shoes (or No Shoes) in U.S. Cavalry History, Part 1

Wednesday, December 26, 2012

Horseshoes for the US Army: A 300-mile march on pavement tested calks for artillery horses

How--and why--did the US Army make its decision about horseshoe policies in days gone by? The advent of paved roads in the 1920s necessitated a reaction from the Army. They realized that, in the event of war or a domestic crisis, artillery guns would be transported over pavement, and the horses' feet would have to accommodate hard-surfaced roads of different types.

The November-December 1935 edition of The Field Artillery Journal tells us about it; an account is transcribed here in red:

The First Battalion, 16th Field Artillery stationed at Fort Myer, Virginia, recently completed a march from its home station to the concentration area of the First Army Reserve at Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, and return to Fort Myer, Virginia.

- Total distance covered, 301.3 miles.

- Average march per day, 18.7 miles.

- Speed varied between 4 and 5 miles per hour.

Horses were changed daily within the teams and sometimes by spare animals. Also the changing of complete teams from gun to caisson helped to equalize the loads. The use of Hippo Straps was resorted to upon suspicion of a sore neck and before the actual sore was apparent.

The shoeing problem presented many difficulties. Horses that walked with a drag walk--that is that would slide their feet over the road--soon wore out their shoes. Some animals would wear out a set of shoes in one day's march, others in two days, and practically all animals had to be shod within a week's time.

It was discovered that by building up a toe calk and heel calks to the same level on each shoe that they would last much longer. Caution had to be taken that heel calks did not wear down faster than the toe calks, thereby throwing the foot out of level. In one battery, 33 horses were shod in a 24-hour period.

As evidence of the splendid work done by the horseshoers, there was no case in which an animal cast a shoe during the entire march.

Another difficulty encountered was slippery roads. These were a serious menace to both animals and men and such roads should be avoided where possible. Roads of this nature are extremely difficult to recognize by motor reconnaissance. Even after stopping your car and making a very careful examination of the road surface it's a two-to-one bet that you are wrong and your nonslippery road will turn out to be something like an ice skating rink.

By experience in selection of routes this much can be said: Slippery roads usually have a high crown, that is the sides of the road slope off rather steeply, they are always made of a mixture of stone and asphalt or stone and some tar product. The appearance of the surface is most deceptive. It may appear rough or smooth and still be slippery. The presence of asphalt or tar on this surface is a sure sign of danger.

Concrete highways were found to be excellent and no slipping occurred on this type of road except where an unusual amount of repair work with tar or asphalt had been carried out.

Certain new types of asphalt pavement--such as that now being laid in Maryland on some of its state roads and the city of Washington, D.C.--make excellent footing for horses. In fact it proved to be the best type of hard surface on which to march.

The results accomplished are attributed mainly to the following reasons:

- A thorough reconnaissance and careful selection of routes;

- The time of day selected for the march;

- The close supervision of the care of animals;

- The care taken to insure a sufficiency of water for animals;

- The superior work of the horseshoers;

- Gaits maintained throughout the march.

To calk or not to calk? That was the Army's question.

Looking at these findings in hindsight, there is no discussion about any benefit or down side of raising the horse's foot off the ground with the calks, or what effect the calks may have had on the horses' foot landing patterns.

It seems the goal was to decrease the amount of time between shoeings by increasing the wear that the shoe could provide.

The author also does not comment on whether the horses had better or worse traction on different types of pavement encountered based on whether they were flat shod or shod with calks.

This video shows an artillery team in action during the National Cavalry Competition in 2011 at Fort Reno in Oklahoma; this is a unit from Fort Sill, also in Oklahoma. (Photo via U.S. Army Veterinary Corps Historical Preservation Group)

No followup to this article was published so it's difficult to know if the calked shoes were adopted for permanent use on the horses, or how they fared.

It was often Army policy to adopt a method of hoof trimming or one specific shoe, such as the Army's decree that the Goodenough shoe be tested on 50 percent of Army horses in the years following the Civil War. No criteria were given about which horses were best suited to that type of shoe; the goals were efficiency in stocking and procurement, economy in purchasing large quantities, and finding a shoe that offered maximum wear qualities.

Influential men all the way up to US Presidents were courted to adopt various shoe designs or trim methods for use by the US Army. The Civil War was barely ended before General Ulysses S. Grant was recommending a complete overhaul of how the US Army shod its horses. He recommended the adoption of the Dunbar system to Quartermaster Montgomery Meigs. It literally took an Act of Congress to change horseshoes for the Army, but Dunbar and Grant accomplished it.

While it seems insensitive to the horses to make judgments based solely on the longevity of a steel shoe, the Army had very practical decision-making systems that would be based on what would happen during a war situation, where the loss of a horse from work because of needing re-shoeing, or the loss of shoes, or the quick wear of shoes might affect the ability of the battalion to move the guns to new positions.

Another question this brings to mind is that calk-heeled shoes certainly weren't new. Removable calks were available commercially, as well. It is interesting that the military had been using flat shoes previously, although the reason behind that preference isn't stated--and might have been a good one to ask.

While it seems insensitive to the horses to make judgments based solely on the longevity of a steel shoe, the Army had very practical decision-making systems that would be based on what would happen during a war situation, where the loss of a horse from work because of needing re-shoeing, or the loss of shoes, or the quick wear of shoes might affect the ability of the battalion to move the guns to new positions.

Another question this brings to mind is that calk-heeled shoes certainly weren't new. Removable calks were available commercially, as well. It is interesting that the military had been using flat shoes previously, although the reason behind that preference isn't stated--and might have been a good one to ask.

Were calked shoes the answer to the Army's problem? Could a modification that extends shoe wear also be guaranteed to prevent slipping? There's more than one way to calk a horse, and the Army chose the most labor-intensive method: having the horseshoers (the US military did not the use of the word "farrier") forge them in the fire as part of the shoe, and from the same material. When a calk was worn, the entire shoe would need to be replaced. How efficient was that?

If you like what you read on The Hoof Blog, please sign up for the email service at the top right of the page; this insures that you will be sent an email on days when the blog has new articles.

--story © Fran Jurga

If you like what you read on The Hoof Blog, please sign up for the email service at the top right of the page; this insures that you will be sent an email on days when the blog has new articles.

Thanks to the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps Historical Preservation Group for their mention of the horseshoe wear study of the Fort Myers unit.

To learn more:

Historic Hoofcare: Ice Harvesting (special shoes for winter traction)

|

| Click here to receive free hoofcare news alerts from The Hoof Blog. |

by John Kiernan, Chief Farrier of the Cavalry Depot, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Follow Hoofcare + Lameness on Twitter: @HoofBlog

Read this blog's headlines on the Hoofcare + Lameness Facebook Page

Disclosure of Material Connection: I have not received any direct compensation for writing this post. I have no material connection to the brands, products, or services that I have mentioned, other than Hoofcare Publishing. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

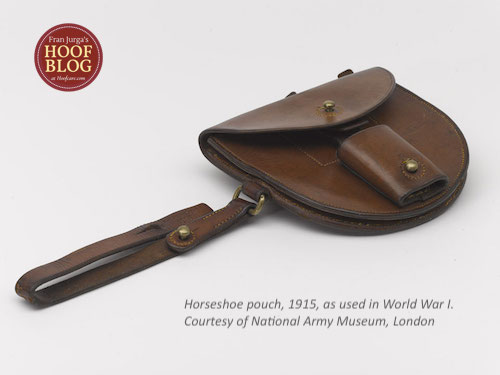

War Horse Hoofcare: Keep Your Eye on the Galloping Horseshoe Pouch

And keep your eye on the bouncing horseshoe pouch.

|

He's a British cavalry horse. It's World War I. He's lost his rider and he's behind German lines. The horse is running for his life, blindly through the forest.

Do you notice anything interesting about his tack?

Most people are arguing about whether the runaway scene through No Man's Land toward the end of the film (the one shown repeatedly on television trailers) was done with edited tack. Surely his stirrups were removed or they would have caught on something in all that debris the horse encountered. And a real horse would have stepped on his reins, they say.

But some of us were straining to see if the horseshoe pouch had found its way back to the saddle. This leather case was designed to carry two spare horseshoes and 12 nails. The case was attached to military saddles; every horse went forward with spare shoes and nails. And Steven Spielberg's crew was detail-oriented enough to make sure that the traditional pouch is attached to the saddle.

Horseshoe pouches can be pricey; Ken McPheeters' Antique Militaria has two American ones (one is shown below) for sale, one pre- and one post-Civil War. They start at $1000. There is a double pouch for shoes and brushes.

|

| How considerate of the actor who played Captain Nicholls, Tom Hiddleston, to lift his arm and reveal the horseshoe pouch (circled) in this still image from the film. DreamWorks Pictures image. |

Horseshoe pouches can be pricey; Ken McPheeters' Antique Militaria has two American ones (one is shown below) for sale, one pre- and one post-Civil War. They start at $1000. There is a double pouch for shoes and brushes.

When you opened the case, this is what you would have seen (see photo): a small pocket for nails and usually two horseshoes. I think someone needs to make a nice horseshoe for this nice old case, unless maybe the old used shoe shown here has historical significance.

Some cases had a loop on the outside that held a saber where it would not impede the movement or comfort of the rider but where it could easily be reached and drawn. The pouch in War Horse did not have that loop, although the one in the photo from the National Army Museum does have it.

Throughout War Horse, the attention to detail in the uniforms and horse equipment is admirable. Once the horse goes to war, the experts were on the set. Of course, there are always disagreements about what is accurate, since there were so many variations over the course of history.

The horseshoe case was one little detail among many but it's an important one to get right. And they did.

Links to US military horseshoe pouches for sale by Ken McPheeters:

http://www.mcpheetersantiquemilitaria.com/04_horse_equip/04_item_022.htm

http://www.mcpheetersantiquemilitaria.com/04_horse_equip/04_item_012.htm

Some cases had a loop on the outside that held a saber where it would not impede the movement or comfort of the rider but where it could easily be reached and drawn. The pouch in War Horse did not have that loop, although the one in the photo from the National Army Museum does have it.

Throughout War Horse, the attention to detail in the uniforms and horse equipment is admirable. Once the horse goes to war, the experts were on the set. Of course, there are always disagreements about what is accurate, since there were so many variations over the course of history.

The horseshoe case was one little detail among many but it's an important one to get right. And they did.

TO LEARN MORE

Links to US military horseshoe pouches for sale by Ken McPheeters:

http://www.mcpheetersantiquemilitaria.com/04_horse_equip/04_item_022.htm

http://www.mcpheetersantiquemilitaria.com/04_horse_equip/04_item_012.htm

More about horseshoe pouches:

http://www.sportingcollection.com/blog/?p=222#comments

Much more about War Horse: Fran Jurga's War Horse News blog

Disclosure of Material Connection: I have not received any direct compensation for writing this post. I have no material connection to the brands, products, or services that I have mentioned, other than Hoofcare Publishing. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.

http://www.sportingcollection.com/blog/?p=222#comments

Much more about War Horse: Fran Jurga's War Horse News blog

|

| Click here to add your email address to the Hoof Blog news list. |

Questions or problems with this blog? Send email to hoofblog@gmail.com.

Read more news on the Hoofcare + Lameness Facebook Page

Sunday, January 11, 2009

World War II: Spike Jones' comic horseshoer, beach patrols by horseback, and a Chinese horseshoeing school

Here's a bit of horseshoeing history disguised as entertainment. The catchy Blacksmith's Song 1942 video posted today was created by Spike Jones, who plays the role of the bare-chested horseshoer. You have to love the desktop anvil!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)